Contents

How Data Flows and Digital Technologies Drive Economic Growth. 6

What’s at Stake for Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam. 7

How Each Country Succumbs to the Allure of Data Localization. 11

Bangladesh: Buying Into All of Data Localization’s False Promises 11

Hong Kong: Openness Threatened by Mainland China’s Drive for Control 13

Indonesia: Simultaneously Taking Steps Forward and Backward. 14

Pakistan: Broad Political and Security Concerns Fuel a Drive to Control Data. 14

Vietnam: Trying to Balance Digital Openness and Strict China-Like Controls 16

Previous Research on the Consequences of Data Localization. 17

How ITIF Modeled the Economic Costs for the Countries in This Study 18

Data Restrictiveness Linkage 21

Detailed Findings for Each Country 25

Use the Right Conceptual Framework for Data Policy 27

Acknowledge That Data Localization Imposes Economic Costs 28

Recognize That Controlling Data Is Both Impractical and Counterproductive. 29

Focus on the Fundamentals of ICT Adoption. 29

Adhere to the Accountability Principle. 31

Adopt Global Tech Standards, Accreditations, and Best-in-Class Tools for Government 32

Adopt Model Agreements to Support Law Enforcement Access to Data. 33

Provide a Clear and Level Playing Field for Digital Payments 34

Appendix A: Data Localization Policies in Each Country 35

Draft National Cloud Policy 35

Draft Personal Data Protection Bill 38

The Cyber Crimes Law and Removal and Blocking of Unlawful Online Content 39

Decree 72 on Content Moderation. 41

Personal Data Protection Decree 41

Appendix B: Detailed Modeling Methodology 42

Previous Analysis and Best Practice Modeled. 42

Comparing This DRI With the DRI in Cory and Dascoli’s 2021 Paper 45

Composite Index: Data Restrictiveness Linkage 46

Country-Level Data Restrictiveness Linkages 48

Selection of Response Variables 48

Regression for Trade Volume. 49

Regression for Unit Import Value. 50

Regression for Nontariff Trade Costs 50

Estimating the Effects of Data Restrictiveness on Productivity 50

Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam each have different digital economies, yet they all stand at the same critical crossroad: either implementing core building blocks to support digital development and trade by allowing cross-border data flows or prioritizing control and protectionism by enacting restrictions that stop seamless data flows—a concept known as “data localization.”[1] This choice lies at the heart of two contrasting visions—one looks outward to embrace the enormous opportunity of the global digital economy through cooperation and interoperable laws, while the other looks inward in a costly, misguided, and nationalistic pursuit of control and protectionism. Instead of the latter, policymakers should pursue a data governance framework that addresses legitimate public policy concerns—such as privacy, cybersecurity, and government access to data—in a smart and balanced way that does not fall prey to the false allure of data nationalism. While data localization may only be one part of the much broader, complex puzzle policymakers in these countries and territories face in getting their respective digital development plans right, it is a foundational one. Data flows will only become even more important as the global economy continues to digitalize, and whether countries recognize and embrace this central point as part of smart data governance will be both telling and consequential.

Data will flow across borders unless governments enact restrictions. While some countries allow data to flow easily around the world—recognizing that legal protections can accompany the data and that local and international laws and agreements help ensure firms provide governments with access to data for legitimate purposes—many have enacted new barriers to data transfers that make it more expensive and time consuming, if not illegal, to transfer data overseas. It’s obviously fair and legitimate for these countries to enact or update laws and regulations to address privacy, cybersecurity, regulatory and financial oversight, law enforcement access to data, and other issues. But false and costly “data nationalism” policies not only do not address their stated aims—whether they’re used in the name of privacy, cybersecurity, digital development, or regulatory oversight—but also impose broad and significant costs on national and regional economies. They are also counterproductive, as they preclude the much-needed international cooperation and legal agreements to address legitimate issues between countries as it relates to data. Unfortunately, many policymakers in the countries covered in this report have recently enacted, or are considering, laws and regulations that enact data localization practices.

Data localization is just one aspect of the digital development puzzle—and countries that embrace this misguided approach only set themselves back in the global digital economy.

The economic stakes are high. COVID-19 drove digital adoption in these countries, just as it did around the rest of the world. For example, a World Bank-Shopee survey of 15,000 digital merchants in Indonesia shows that 80 percent remained open when COVID first hit in 2020, 25 percent started their online business during COVID, and, on average, total sales rose to pre-pandemic levels around six months after the first peak of cases.[2] This is indicative of the impact of digital technologies and the opportunities for global connectivity. The absence of restrictions on data flows and the information and digital goods and services they deliver has played a role in helping each of these countries make the remarkable progress they’ve achieved in helping more people and businesses get online and benefit from data, digital technologies, and global connectivity.

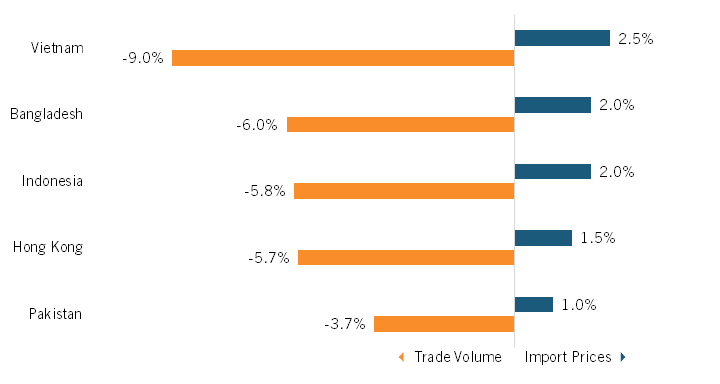

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation’s (ITIF’s) econometric modeling ranks proposed and enacted localization measures in Vietnam as the most restrictive, followed by Bangladesh, Indonesia, Hong Kong, and Pakistan. The model projects that data localization policies currently enacted or under consideration will reduce trade volumes and imports and increase import prices in all these countries and territories.

Figure 1: Projected change in import prices and trade volumes after five years due to restrictive data policies

These changes in both trade volume and the prices of key inputs involved in trade flows will inevitably impact both economic productivity and exports, as data-related goods and services are critical inputs. These results are consistent with a growing body of research from the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD), the World Bank, academia, and other think tanks: Data localization and other restrictive digital policies undermine the growing impact data-intensive services and technologies have on economic productivity and innovation—and by extension, trade. As it reflects a central point for digital economic policy, an economy is most productive and innovative when individuals and firms can engage in digital activity and commerce without unnecessary restrictions on how they can use and transfer data.

Many policymakers focus on the location of data storage, in part, because addressing the underlying factors that actually address associated issues is more complex and challenging. For example, with data privacy, consumer protection, and law enforcement access to data for cross-border investigations, it’s much harder to build the expertise and institutional capacity in government to properly address these concerns and enforce local laws. Likewise, with cybersecurity, it’s challenging to build cybersecurity awareness among users and firms and encourage firms and government agencies to adopt and remain committed to best-in-class cybersecurity practices and services.

Enacting smart data governance frameworks and outcomes is challenging given the stakeholders and interests involved. People need to have confidence that their personal data is respected and protected. Government agencies need to know that they can access the data they need for legitimate purposes, such as consumer protection, financial oversight, and law enforcement investigations. Businesses need to know what they need in order to be accountable in collecting, protecting, and using both personal and nonpersonal data. This complexity is especially challenging for policymakers in developing countries who often lack the resources and expertise to help craft effective digital policies. However, there are many countries, development agencies, and other organizations to work with, and best practices, norms, and principles to learn from, to help countries build smart data governance policies.

This report highlights why localization policies in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan, Vietnam, and Hong Kong are both costly and misguided. It aims to help policymakers in these countries and territories recognize what’s at stake in avoiding the pitfall that is data localization and how there are alternatives that address associated public policy concerns without unnecessarily incurring self-inflicted data localization costs. The first section of this report analyzes the central role of data and digital technologies in economic development and summarizes what’s at stake in getting future digital policies right given the considerable progress each of the countries and territories has made in advancing their digital economies. The second section analyzes each country’s misguided attraction to data localization, as while there are similarities, the prevailing motivations for data localization differ by country and territory. The third section provides a quantitative assessment as to the considerable economic impact of data localization in these countries and territories. The final section provides recommendations, while Appendix A includes a list of data localization policies and Appendix B provides details of the econometric methodology.

No matter a country’s level of development, data is critical to economic development. Access to affordable and high-quality information communication technologies (ICTs) is one of the modern economy’s chief drivers of productivity, innovation, and economic growth. ICTs are such powerful tools precisely because they represent a general-purpose technology that enhances the productivity and innovative capacity of every individual, enterprise, and industry they touch throughout an economy. Policies that make ICTs more expensive, or simply cut off access to best-in-class ICTs, thereby introduce a broadly negative economic impact. This points to the central way ICT drives a country’s economic growth, which is not through the production of ICT goods (i.e., the manufacturing of computers or smartphones or design of software). Rather, the vast majority of the economic benefits generated from ICT, especially in developing countries, stems from greater adoption of ICT across an economy.[3] As Richard Heeks, professor of development informatics at the University of Manchester, estimated, “ICTs will have contributed something like one-quarter of gross domestic product (GDP) growth in many developing countries during the first decade of the 21st century.”[4]

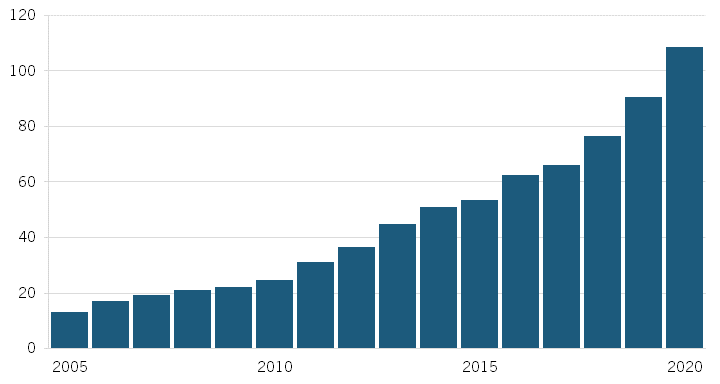

The economic impact of ICTs only grows as global trade becomes increasingly digital. The Internet has not only removed the impact geography had on trade—in that, in traditional 20th century trade, firms from any of the countries in this study would’ve traded little, if at all, with customers from countries on the other side of the world—but the increasingly digital nature of trade makes it easier for firms and workers around the world to engage in services trade.[5] The unbundling of trade has made services an increasingly important component of economic activity, both as tradable “products” in and of themselves and as intermediate goods in the network of production and trade in goods and services.[6] The two interrelated trends—increased digitalization and increased unbundling of services—have created a global market for services tasks that has contributed to the tripling of services trade over the past 15 years, particularly for business services such as legal, advertising, consulting, and accounting.[7] From 2005 to 2019, global exports of digitally deliverable services grew at an average nominal rate of 12 percent per year and at a rate of as much as 21 percent in Asia. The share of digitally deliverable services in total global services exports had already increased from 45 percent in 2005 to 52 percent in 2019.[8] As the following section details, many of the countries and territories in this study are early beneficiaries of this digital evolution in trade and commerce.

Each of these countries and territories has made truly remarkable progress in helping more people and businesses get online and benefit from data, digital technologies, and global connectivity. Table 1 shows that while Bangladesh and Pakistan are at a similar level of digital development, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Hong Kong are at different levels. Whatever their similarities, local political, economic, legal, and social factors also mean they each face their own path ahead to further digital development. Obviously, a lot more remains to be accomplished in helping address the digital divide and other digital development issues in these countries and territories. However, it’s important to highlight the progress they have made in the following summaries so as to recognize what’s at stake in considering data localization and the need to not enact localization policies in order to get the next phase of digital policy right.

Table 1: Comparative global rankings in key indices of digital development[9]

|

Index |

Bangladesh |

Hong Kong |

Indonesia |

Pakistan |

Vietnam |

|

UNCTAD B2C E-commerce Index (152 economies) |

115 |

10 |

83 |

116 |

63 |

|

ITU ICT Development Index (176 economies) |

147 |

6 |

111 |

148 |

108 |

|

WEF Network Readiness Index (130 economies) |

95 |

32 |

66 |

97 |

63 |

Bangladesh’s digital economy shows enormous promise. The government’s “Digital Bangladesh” vision has set the foundation for its digital economy, along with subsequent initiatives and policies such as the A2I initiative, the National Digital Commerce Policy 2018, and the National ICT Policy 2019. The digital economy constitutes a significant national development opportunity for Bangladesh and a chance to diversify from traditional industries prevalent in the country.[10] The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimated that, since 2010, Bangladesh’s ICT sector has grown at an astonishing average pace of 40 percent annually.[11]

Bangladesh has not only performed well at home but also globally in taking advantage of the digitalization of trade. Over the past 15 years, the average annual growth rate of IT and IT-enabled services exports was more than 15 percent against 13.6 percent growth in nominal GDP. There’s enormous room to catch up. Bangladesh’s services export-GDP ratio is just 1.5 percent, compared with around 40 percent in India, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka.[12] The domestic and export growth no doubt contributes to Bangladesh’s efforts to attract considerable foreign direct investment (FDI) from Malaysia, the United States, India, and Norway. In 2019–2020, the ICT- and IT-enabled services sector attracted $758 million in FDI.[13]

Despite myriad development challenges, Bangladesh has performed remarkably well in taking advantage of digital commerce at home and globally.

Bangladesh possesses a fast-evolving e-commerce sector, driven by a flourishing ICT sector and a fast-growing middle income consumer base, which has become accustomed to using modern ICT services. For example, usage of Facebook for commerce (known as “f-commerce”) is widely popular in Bangladesh. In 2017, the eCommerce Association of Bangladesh estimated that there were many more Bangladeshi e-commerce Facebook pages (7,000) than formal e-commerce websites (700). In many cases, these allow buyers and sellers to interact online but having to conclude transactions offline. This informal activity is estimated to be significantly larger than the number of formal e-commerce transactions.[14] All this progress is significant, but so are the remaining hurdles. A recent, thorough UNCTAD Rapid eTrade Readiness Assessment of Bangladesh points toward the need to improve telecommunication infrastructure, trade logistics, payment solutions, laws and regulations, and skills.[15]

Hong Kong is different from the other countries in this report given its status as a special administrative region of China and the fact that it already has many enviable advantages—it has an advanced digital economy and society and is a central business hub for the Asia Pacific and mainland China. For example, over 95 percent of households have broadband Internet and own a smartphone; 86 percent of consumers use social media for an average of nearly two hours per day; and following credit cards, digital wallets are the second-most popular payment option (at 25 percent).[16] Hong Kong’s success is due in no small part to the government’s extensive, sophisticated digital policy plans.[17] Hong Kong’s digital policy is also a critical component of China’s development plans for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area initiative and as a Digital Command Hub for China’s Digital Belt and Road strategy. [18]

An emphasis in Hong Kong’s 2022 budget is promoting innovation and technology development. In order to accelerate the progress of its digital economy, the government will set up a “Digital Economy Development Committee” in support of building Hong Kong into an international innovation and technology hub, which is a goal of China’s 14th Five‑Year Plan. Hong Kong’s budget includes extensive plans and capital to build out its tech economy and expand the use of digital technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data, blockchain, cloud computing, and cybersecurity.[19] Yet, as this report analyzes, the central challenge for Hong Kong is how to balance efforts to maintain its position as a digital-savvy tech hub with mainland China’s growing efforts to exert a greater degree of control over the region’s digital life and economy with vague and restrictive cybersecurity and national security laws.

Indonesia holds enormous promise in developing its large, dynamic, and tech-savvy domestic digital economy into a leading regional and global digital economy. President Joko Widodo clearly recognizes this potential and has stated his goal for Indonesia to become both a major market and a player in digital technologies at home and in the global digital economy.[20] In 2020, Indonesia’s estimated e-commerce gross merchandise value was $32 billion, an increase of 54 percent from 2019.[21] One study estimates it could grow to reach $146 billion by 2025.[22] Again, as the other countries in this report, huge challenges—but also benefits—remain.[23] Nearly half of Indonesian adults are not connected to the Internet and there’s a gulf across spatial, economic, and social dimensions.[24] In 2019, the proportion of Internet-using households that reported buying and selling online was 12.8 and 5.1 percent, respectively.[25] Indonesia’s government is focused on addressing these issues. For example, the government of Indonesia, has launched the MSMEs (micro, small-, and medium-sized enterprises) Go Online program, which provides capacity-building to expedite digitization.

Digital development has already proven enormously beneficial to Pakistan.[26] The country produces more than 20,000 IT graduates annually, has seen over 700 tech start-ups launched since 2010, and has the fourth-highest-earning information technology (IT) workforce in the world.[27] Pakistan’s technology sector represents a large and fast-growing exporter, with annual revenue from exports of IT and IT-enabled services accounting for $1.4 billion in 2020 (having grown at 10.8 percent per year since 2010).[28] Much of this is based on surging Internet connectivity, particularly via smartphones, penetration of which has increased from approximately 6 million in April 2014 to nearly 80 million by December 2019.[29] Obviously, Pakistan still has many challenges to address in order to extract economic and societal benefits from data and digital technologies. There’s a growing digital divide, in part due to relatively high Internet costs.[30] Digital literacy is limited, and digital adoption by the government is lower than that of its regional neighbors. Pakistan’s government, development agencies, and private sector have introduced strategies, investments, and policies to support and expand the impact of digital technologies, such as via the Digital Pakistan Policy, the Pakistan Software Export Board’s software technology parks, and the World Bank’s digital connectivity program.

Vietnam holds enormous potential to leverage data and digital tools to bolster its growing and dynamic consumer digital market alongside its role as a central part of global production networks.[31] Data and digital services will be critical to Vietnam’s efforts to move from low-tech manufacturing to a higher-value-added manufacturer and service-oriented economy. The potential is clearly there. Vietnam’s digital economy has grown 16 percent from 2019 to $14 billion, which places it among the biggest digital markers in Southeast Asia.[32] Vietnam is playing a growing role in high-tech production, with high-tech goods as a share of exports hitting 42 percent in 2020, up from 13 percent in 2010.[33] In particular, Vietnam has the opportunity to capitalize on firms looking for an alternative to China given that nation’s trade dispute with the United States and restrictive approach to data governance and cross-border data flows.[34]

To its credit, Vietnam recognizes the need to build digital connectivity with its trading partners, such as via the data and e-commerce provisions in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) trade agreement. Vietnam has also enacted a series of thoughtful strategic plans and policies to support digital development, including its National Digital Transformation Plan and ongoing efforts to design a National Strategy on the Digital Economy and Society. It is also engaged, sometimes in a leadership role, in building digital governance with its Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) partners, such as via the APEC Da Nang Declaration and the ASEAN Digital Masterplan 2025.[35] There are many issues Vietnam needs to address to develop digitally, such as issues with skilled labor, good and secure access to information, and efforts to promote e-learning, e-payments, and e-government.[36] But this hasn’t stopped Vietnam from considering potential broad and harmful data localization policies. While data flows represent just one aspect of these plans and Vietnam’s digital economy, it is a key one, especially given the country’s development goals and reliance on global trade, investment, and connectivity.

Case Study: Global Gig Work and Services Exports in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam

Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam are playing a growing role in global services exports. For example, Bangladesh is the world’s second-largest source of online labor (after India), accounting for about 15 percent of global Internet workers.[37] It has a growing freelancer sector with a half-million people actively participating in the global gig economy. According to Bangladesh’s ICT minister, its online workers earn around $500 million every year.[38]

Meanwhile, Pakistan currently is the fourth-largest provider of workers to online freelancing platforms globally.[39] Oxford’s Online Labour Index 2020 provides a broader picture as it tracks all the projects/tasks posted on the five largest English-language online labor platforms, representing at least 70 percent of the market by traffic. It shows that Bangladesh is home to the 2nd-largest group of global gig workers (15 percent), followed by Pakistan in 3rd (12 percent), with Indonesia in 12th (1.4 percent).[40]

Most gig workers in Bangladesh and Indonesia are involved in creative and multimedia work, while most in Pakistan and Vietnam are involved in software development and tech service work.[41] International gig work opens up opportunities for more women to get involved, and overall pays better than do other sectors.[42] The geographic spread of these jobs across nations also highlights how countries are competing to have as many of these workers as possible and how policies that make this harder and more expensive will inevitably lose out.

Policymakers in Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam have used a variety of misguided motivations in considering and enacting data localization policies. Appendix A provides a detailed list of all their enacted and proposed data localization measures. The following section provides analytical context for these measures. While there are similarities, they also differ in some important ways. This analysis points to the constructive alternatives (as detailed in the recommendations) to data localization that are available to each country in an effort to help them shape smart data governance policies.

Bangladesh is learning many of the worst lessons from its neighbors in China (and also India) when it comes to enacting restrictions on data transfers for misguided data privacy, cybersecurity, law enforcement, and national security reasons.[43] This is clearly evident in its draft data protection act and national cloud policy.[44] Bangladesh’s draft data protection act is misguided not only due to its data localization measures, but also because it conflates privacy and content moderation in a way no other countries do in not only forcing firms to store sensitive data locally but also the broad (and practically infeasible) category of user-created or generated data.[45] It’s a particularly dangerous and costly path for Bangladesh (as compared with India and China, never mind Indonesia and Vietnam) to follow, as while it is a promising emerging digital market, it is relatively small and thus most likely to result in firms avoiding, withdrawing, or downgrading services and market operations in the face of uncertain, onerous, and costly digital restrictions.

Key Bangladeshi policymakers prioritize state control over data, data flows, and digital technologies over other associated economic, social, and legal interests. By control of data, what they tend to mean is an idealized, but ultimately unrealistic, ability to have unfettered access to it.[46] They hope such policies will help Bangladesh take back control and provide sovereignty from foreign technology firms and governments and force them and foreign governments (namely, the United States) to force firms to hand over data. This is part of both Bangladesh’s draft data protection bill and cloud strategy.[47] Beyond local security and political concerns, geopolitical risk is also a factor in Bangladesh. In 2021, U.S. human rights sanctions against the government’s “Rapid Reaction Battalion” led to an upswell of nationalism and protectionism that included support for localization.[48]

Bangladesh is learning all the worst lessons from China regarding data localization and digital control.

Bangladeshi policymakers focus on the location of data storage instead of the legal and institutional structure and processes that facilitate legitimate, efficient, and legal access (both domestically and internationally). Bangladeshi authorities are frustrated that U.S. companies—like all firms from rule-of-law countries—manage requests for data from governments according to laws in their home country and as specified under legal agreements between countries (e.g., Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs)). If requests from Bangladesh don’t meet set legal criteria, firms can’t provide access to data. This is made that much harder, as there isn’t a U.S.-Bangladesh MLAT. It’s fair to criticize MLATs and other traditional mechanisms for law enforcement data exchanges as outdated, slow, and frustrating, but this is why this should be the focal point for action. Localization is not the silver bullet some policymakers think it is. Firms don’t manage user data by some name-by-name traditional filing system. Any one user or activity will likely involve multiple intermediaries, people, and jurisdictions. The digitalization of crime means law enforcement needs for cross-border cooperation will only increase. Hence the need for updated legal tools.

Bangladeshi policymakers also try to justify localization as necessary to protect commercial and government data. They believe data is more private and secure when it is stored within a country’s borders. However, in most instances, data-localization mandates increase neither commercial privacy nor data security.[49] Companies doing business in a nation—all domestic companies and most foreign—have “legal nexus,” which puts the company in that country’s jurisdiction. For example, a global bank or manufacturer that has branches or plants in a nation is subject to that nation’s privacy and security laws and regulations. Companies simply cannot escape from complying with a nation’s laws by transferring data overseas. Wherever there are cross-border jurisdictional issues (as all firms that manage data from multiple countries manage multijurisdictional issues and tend to apply a single approach to all), again, the focus needs to be on the tools and capabilities and how to use them effectively.

As much as it relates to cybersecurity and surveillance, policymakers misunderstand that the confidentiality of data does not generally depend on which country the information is stored in, but rather only on the measures used to store it securely. A secure server in Bangladesh is no different from a secure server in Malaysia. Data security depends on the technical, physical, and administrative controls implemented by the service provider, which can be strong or weak, regardless of where the data is stored. For sensitive government data and services, governments can specify in their procurement contracts that providers must use the latest cybersecurity standards and encryption, or other advanced protective measures.

Policymakers focusing on geography to solve privacy and cybersecurity concerns are missing the point. Consumers and business can rely on contracts or laws to limit voluntary disclosures to ensure that data stored abroad receives the same level of protection as data stored at home. In the case of inadvertent disclosures of data (e.g., security breaches), to the extent nations have security laws and regulations, again a company operating in the nation is subject to those laws, regardless of where the data are stored. Moreover, security breaches can happen no matter where data is stored—data centers everywhere are exposed to similar risks. What is important is that the company involved (either a company with its own networks or a third-party cloud provider) be dedicated to implementing the most-advanced methods to prevent such cyberattacks. The location of these systems has no effect on security.

Bangladesh’s policymakers fail to recognize that foreign cloud and digital service providers only deploy data centers sparingly and that it simply doesn’t make sense to deploy IT systems in each and every market. Never mind the fact that the location of data and data centers does not lead to digital development. Some policymakers in Bangladesh focus on data centers, in part, because they are misguidedly attracted to a data localization-based digital sovereignty, as they mistakenly think “data is the new oil.” While it is certainly true that data has become invaluable, the oil analogy is fundamentally flawed (see the Recommendations section of this report).[50] Policymakers should understand how data is transforming the economy, but looking to oil as a historical example is not productive.

Hong Kong’s government is under pressure from mainland China (the world leader in data localization and digital control) to enact restrictions on data flows in the name of “cybersecurity.”[51] This is in addition to other new laws that impact data and digital content, especially its National Security Law. The problem is that China equates cybersecurity with national security, and national security with regime security. This is a profoundly different conceptualization of cybersecurity and national security from that of most countries.

Hong Kong’s government is cognizant of the risk localization poses to its position as a regional and global business hub—which is already under threat from other legal and political issues created by China—and has therefore been considering far narrower data localization requirements (as compared with the broad impact mainland China’s cybersecurity law has on data transfers). Whether a narrow approach to localization will satisfy Beijing is a major question. Hong Kong has been talking with certain foreign firms (namely, firms that operate on the mainland and are therefore familiar with its localization requirements) about this new cybersecurity proposal.

However, it’s a fundamental misreading of the situation if Hong Kong thinks narrow localization will not send another troubling signal to global businesses. This should be clear given the reaction to the National Security Law, which caused many large tech firms to draw down operations in Hong Kong and shift future expansion to other countries.[52] But it’s not just the National Security Law and cybersecurity law. For example, the Cyberspace Administration of China is enacting regulations that would make mainland companies seeking initial public offerings in Hong Kong subject to a cybersecurity review on national security grounds. It is the first time the government said such reviews would apply to listings in the city.[53]

Beijing’s fears of political control are pushing Hong Kong to consider data localization for supposed “cybersecurity-related” reasons.

Hong Kong’s new National Security Law is the clearest example of Hong Kong’s shift to greater digital restrictions.[54] Until recently, Hong Kong’s Internet had been uncensored and unrestricted. One example of this is people in Hong Kong have long been able to access services and apps blocked in the mainland, such as Facebook and Google. The National Security Law moves its Internet within China’s censorship and government access apparatus. China wants to use the National Security Law and a new cybersecurity law to ensure it retains the legal and technical capability to intervene, access, and control data and digital content and communications. In 2019, Hong Kong’s government made just over 5,500 requests for user data and 4,400 requests for removal of content.[55] However, this likely doesn’t capture the full extent of such requests, as investigations into national security crimes can be deemed a state secret, with any trials potentially heard in closed court and tech companies being forbidden from disclosing what the police ask them for.

One major concern about Hong Kong’s new National Security Law is it targets content removal and access to data on a potentially global basis. While it’s impossible to know how China uses this new law (Macau has had a similar law in place for over a decade and there have been no reported enforcement cases), there’s the potential to see how articles 38 and 43 could be used in this way, as they apply to offenses committed outside Hong Kong and allow authorities to ask the publisher, platform, host, or network service provider to remove or restrict access to the data or produce information about a user.[56] The threat of vague, broad, extraterritorial requests for data will likely force firms to either localize data to ensure they’re in compliance (and thus avoid punishment in Hong Kong, on the mainland, or both) or to simply withdraw, downgrade services to avoid or minimize the potential for major legal and compliance risks in other markets, or both.

Indonesia: Simultaneously Taking Steps Forward and Backward

Despite its enormous digital promise—or perhaps due to it—Indonesia’s digital policy debates often feature data localization proposals. Indonesia has enacted localization measures for public sector entities and banking and nonbank financial institutions; however, to its credit, the country has also removed or reduced potentially broad localization requirements, such as in its new data protection law, in rules for public and private systems operators, and in relation to payments data.[57] The battle to ensure Indonesia adopts further smart data governance policies that support its evolution into an integral part of the global digital economy is far from over. For example, there are fears that Indonesia’s data and digital policies will backslide after being the G20 host in 2022, including as part of implementing regulations for its data protection law and in consideration of enacting duties on digital transmissions.

Indonesia’s motivations for considering data localization vary, but a central one is that it represents the latest iteration of the country’s historical attraction to state-directed, protectionist industrial policy. Many Indonesian policymakers look to China as their model, thinking they too can use their large domestic market and digital protectionism to support locally owned (and often state-owned) operators in its data center, cloud, payment, and e-commerce sectors.[58] For example, Indonesia’s central bank tried (though it eventually backed down) to use localization to favor locally owned payment operators.[59] Indonesian data center operators also publicly supported localization and opposed efforts to remove localization requirements.[60]

It is not too late for Indonesia to enact smart data governance policies to become a leading global digital economy.

Data localization is also featured in debates over cybersecurity and government access to data, including due to concerns about law enforcement access to data held in other countries, such as Singapore. Likewise financial regulatory authorities have used localization due to concerns regarding access to data for regulatory oversight. For example, Indonesia’s Financial Services Authority (OJK) mandates that banks and nonbank financial institutions have data and disaster recovery centers in Indonesia, though some data transfer exceptions apply.[61] Certain Indonesian policymakers also consider localization as part of a misguided effort to improve the data security and privacy of sensitive government data and services, including from foreign government surveillance (e.g., from China).[62]

Similar to Bangladesh, Pakistan is taking all the wrong lessons from India, China, and Russia in considering restrictive data laws and regulations for misguided, and very costly, national security and digital protectionist purposes. Pakistan has enacted several laws and regulations that explicitly and indirectly restrict the movement of data, such as the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA, commonly known as the Cyber Crimes Law) and its draft Personal Data Protection Bill.[63] The impact on domestic and foreign firms will be significant, especially as these laws significantly increase the potential legal risks for firms managing personal data. For example, as appendix A details, PECA goes beyond traditional cybercrimes and criminalizes certain online speech and gives authorities unchecked powers to curtail and prosecute it. Similar to Bangladesh, the misleading appeal of China’s digital control to Pakistan’s policymakers will entail much clearer and greater costs in the latter, as Pakistan simply doesn’t make sense for firms to set up expensive and duplicative IT systems in such a promising, but highly problematic, digital market.

Pakistan’s primary motivation for data localization is national security—namely, its intelligence services want immediate and unrestricted access to data for political, social, and security reasons. Pakistan clearly prioritizes security and political interests over economic and trade interests, as well as human rights concerns. Pakistani policymakers can certainly make that trade-off, but they should be aware of the large economic and trade costs involved. Pakistan’s policymakers also obviously do not want to make this trade-off clear as they try to avoid or minimize debate and scrutiny over their digital and data policies.[64] Pakistan’s commitment to data localization is clear, as it considered and enacted amendments to PECA in 2021 but kept the problematic provisions, including data localization and the need for foreign firms to set up a local office and have local staff based in the country (in order to hold them personally liable for the firms’ compliance).[65]

Pakistan uses localization as a cudgel to force firms to access user data, store data locally, and remove a broad range of digital content. Indicative of this, in relation to PECA, a Pakistani military spokesman boasted in a press conference that the intelligence agencies were able to look into individual social media accounts, thus implying dire consequences—including many years in jail—for posting dissent online.[66] For example, a case under Section 20 of PECA was lodged against a political activist in Lahore accused of propaganda.[67] PECA is particularly problematic due to the lack of legal safeguards and oversight. The rules allow a broad range of state agencies to make confidential requests for content removal through the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA), without any visibility regarding the source of the complaint. PTA is also responsible for hearing reviews and appeals against its own decisions.[68]

Pakistan clearly prioritizes the use of data localization for supposed national security reasons over associated economic, trade, and human rights interests.

Mixed into these security motivations are misguided privacy, cybersecurity, and digital protectionism goals—but these are definitely secondary. For example, in Pakistan’s Draft E-Commerce Policy, it states that “home to the world’s 6th largest population, data generated in Pakistan is a very valuable asset due to its huge size and there is a dire need to ensure that all the data generated in Pakistan is stored and processed in Pakistan as it is primarily ownership of the citizens to whom it relates.”[69] Similarly, it reveals that “ownership of data is determined by location of the data centers where data is stored.”[70] As this report shows, focusing on the limited investment and few jobs that go into local data centers over the broader economy’s growing use of data and digital services is a very costly trade-off. Such misguided data nationalism will only hold Pakistan back, as what matters is having the education, skills, infrastructure, and regulatory environment to help individuals and firms actually use data—regardless of where it’s stored, as what actually matters is cloud access and skills—to use data to actually create economic value.[71]

Vietnam is unique in its use of data localization. Like the Chinese Communist Party, the Communist Party of Vietnam sees localization as a critical tool to assert political control. Yet, it is different, as its efforts to move its manufacturing and services sectors up the value chain economically and via trade agreements means it can ill afford restricting the movement of data. Vietnam has data localization requirements for personal, payments, and a broad range of data managed by social networks, search engines, and other digital firms. Vietnam is also unique in that it faces the real prospect of a trade law challenge (via e-commerce provisions in the CPTPP) if it doesn’t allow the free flow of data.[72] Until Vietnam realizes that it needs a smart data governance strategy that addresses legitimate data privacy, protection, and cybersecurity concerns while allowing data to flow freely, it’ll never fully realize its full digital potential.

Vietnam uses privacy and data protection concerns to justify localization, and while its laws address many legitimate parts of these issues, it’s clear that at the heart of these policies are political and social interests around controlling certain data and digital content.[73] Its institutional arrangements show this; Vietnam’s data protection agency is the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), while in most other countries, there’s an independent, specialized data protection agency. Vietnam’s Law on Cybersecurity (LOC), and its various implementing regulations (namely, Decree 53), gives MPS the authority to request firms to store data locally and set up a local office if they’re judged to not be cooperating with government requests for data and to remove content in a timely manner.[74] It’s just a matter of time to see how extensively MPS uses this authority, and thus how broad the localization requirement will be. Vietnam has also considered an onerous personal data transfer assessment and notification scheme.[75] The country has a de facto localization requirement for payments data, along with other restrictions, to support a state-owned payments firm.[76]

Vietnam wants to attract data-intensive manufacturing and service firms to upgrade its economy, yet it is enacting data localization requirements that undermine this goal.

The main targets of Vietnam’s restrictive data regime are broadly used digital services such as search and social networks, given their role in facilitating social and political discussions. Unlike China with its “Great Firewall,” Vietnam allows foreign social media and search firms to operate, although authorities are making these firms’ operations increasingly difficult via vague and potentially onerous localization and content moderation requirements, such as broad and urgent requests to verify users, remove a broad range of content, and suspend user accounts. Due to the impact on privacy, free speech, and other rights, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have both condemned Vietnam’s Cybersecurity Law.[77]

Similar to China, Vietnam has tied cybercrime and cybersecurity policies (which address legitimate issues) to social and political goals.[78] For example, article 4 of Vietnam’s cybersecurity law designates that “the principle of protecting cyber security [is] under the leadership of Vietnam’s Communist Party.”[79] Article 8 and 15 prohibit “the use of cyberspace [to] prepare, post, and spread information [that] has the content of propaganda opposing the State of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,” or “offends the nation, the national flag, the national emblem, the national anthem, great people, leaders, notable people, and national heroes.” As it relates to traditional nation-state cybersecurity threats, Vietnam is unique in that while it was inspired by China’s cybersecurity law, the country adopted the law in no small part to defend itself against China-backed and -based cyberattacks.[80]

Vietnam will struggle to have it all in terms of being an attractive country for high-tech and digitally intensive manufacturing and services while enacting potential broad, vague, and restrictive restrictions on the flow of data, the digital services they support, and the management of digital content. Removing or severely degrading social and search firms and their services will not only send a clear signal that Vietnam is not truly committed to playing a role in global production networks and the global digital economy, but inevitably impact these and associated digital services used in everyday business for data analytics, communication, marketing, advertising, and support services. Potentially severe criminal and financial penalties (including holding firms’ representatives personally responsible) will cause social, search, and other firms that manage digital content and services to reconsider their operations, selectively engage, or simply not operate there at all. If Google, Facebook, and other large firms struggle to operate in Vietnam, smaller firms that manage some of the same data and content don’t stand much of a chance.[81] It’ll lead to fewer foreign firms and digital goods and services in Vietnam, which will inevitably negatively impact Vietnam’s economy.

The spread of data localization policies in Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam will negatively impact their domestic digital economies. It would also add to the growing threat that localization and other digital barriers pose to the potential for an open, rules-based, and innovative global digital economy. Ultimately, data localization makes the Internet less accessible and secure, more costly and complicated, and less innovative.

Developing an econometric model for the impact of data localization on these countries and territories was challenging, but ultimately worthwhile, in that it shows clear and convincing results about the negative economic and trade impact of data localization. In particular, it was challenging due to the simple fact that not all these countries are included in major trade and economic databases used for this type of econometric modelling. For example, OECD’s Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) database covers only a small number of emerging countries, while the World Bank STRI data is only available periodically, with the latest STRI covering 2016 policies released in early 2020.[82] There is ongoing work to extend coverage and analysis, including via Hoekman and Shephard’s “Services Policy Index,” which extends the OECD STRI to countries included in the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) Integrated Trade Intelligence Portal (I-TIP), but not in the OECD database.[83]

This report contributes to a growing body of research with similar results showing that data localization and other restrictive digital policies undermine the growing impact data-intensive services have on economic productivity and innovation, and by extension, trade.[84] At the country level, in 2014, the European Center for International Political Economy (ECIPE) estimated that economy-wide data localization and other administrative barriers in Indonesia and Vietnam would decrease GDP by 0.7 percent and 1.7 percent and domestic and FDI by 2.3 percent and 3.1 percent, respectively.[85] More recently, in 2022, Research and Policy Integration for Development (RAPID) in Bangladesh performed an interesting study on the economic impact if Bangladesh enacted localization requirements similar to India and Vietnam. In these two scenarios, it estimated that this would decrease digital services exports by from 29 to 44 percent and decrease GDP by 0.6 to 0.9 percent. If its trading partners retaliated in kind, digital service exports would decrease 32 to 37 percent and decrease GDP by 0.76 to 0.9 percent.[86]

Broader economic and trade studies support these country-level results, as restrictive data and digital trade policies negatively impact firms using services as inputs, reduce the competitiveness of services exporters, and increase prices, lower the quality of services available to households, or both. ITIF’s past econometric analysis (2021) of data localization’s general impact estimates that a one-unit increase in a country’s data restrictiveness index (DRI) results (cumulatively, over a five-year period) in a 7 percent decrease in its volume of gross output traded, a 1.5 percent increase in its prices of goods and services among downstream industries, and a 2.9 percent decrease in its economy-wide productivity.[87]

The World Bank’s 2020 World Development Report finds that “restrictions on data flows have large negative consequences on the productivity of local companies using digital technologies… Countries would gain on average about 4.5 percent in productivity if they removed their restrictive data policies, whereas the benefits of reducing data restrictions on trade in services would on average be about 5 percent.”[88] Conversely, in terms of associated digital openness, a 2018 OECD report notes that digitalization is linked with greater trade openness, selling more products to more markets, and that a 10 percent increase in bilateral digital connectivity increases trade in services by over 3.1 percent.[89] While any indicator of services trade restrictiveness should be a strong predictor of bilateral services trade, other recent research shows that because of the input–output relationships that exist between services and other sectors, it’s also likely that services policies affect total trade (i.e., goods and services).[90] Converting Shephard and Hoekman’s “Services Policy Index” to an ad valorem equivalent (i.e., a percentage of the price) shows that services policies are typically much more restrictive than tariffs on imports of goods, in particular in professional services and telecommunications sectors. However, while their model includes Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Vietnam, results are aggregated and not broken down by country.

This section details ITIF’s econometric analysis of the impact data localization would have specifically on Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam. Appendix A includes a full list of data localization policies; appendix B includes details about the model’s methodology.

To estimate the economic impact data localization has on data-reliant industries, ITIF designed a model to observe empirical changes in economic indicators of a country’s industries due to the enforcement of added data restrictions. This section provides a quantitative analysis of the effects of restrictions given the relationship between data flows and economic performance.

While econometric analysis only provides an indicative estimate of the economic impact (given challenges with measurement and data availability), it is still important to do so to reinforce for policymakers the economic and trade costs of restricting data flows.

ITIF’s analysis is unique because it covers a larger sample of countries not covered in past models, utilizes a longer panel dataset than found in other literature, and compares both trade volumes and trade costs as response variables. Further, the index in this model differs from other analyses in that its index’s calculation is most precisely a function of data localization policies (both explicit and indirect) rather than a function of digital regulations. This methodology should give an accurate assessment of the relationship between economic performance and data localization, since the index encompasses far fewer confounding factors that could add error/statistical noise during econometric analysis.

The structure of ITIF’s quantitative study in this report follows the same core analysis conducted in its 2021 report on data localization, whereby a composite index—the data restrictiveness linkage (DRL)—measuring the linkage of a country’s data restrictions to its industries (based on data intensity) is regressed among a set of variables related to volume of trade, consumer prices, and productivity.[91] However, measurements scoring a country’s data flow restrictiveness come from ITIF’s own calculation methodology, rather than through the use of a proxy variable. This report also expands on ITIF’s previous work by conducting data analysis on a sample size inclusive of a wider range of non-OECD economies in Asia. The model conducts an ordinary least-squares regression on separate models that take log transformations of trade volumes, imports, unit import values, and nontariff trade costs on DRL, and then analyzes coefficient estimates in order to assess the changes associated with an increase in data localization measures. These statistical findings are then applied to Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam.

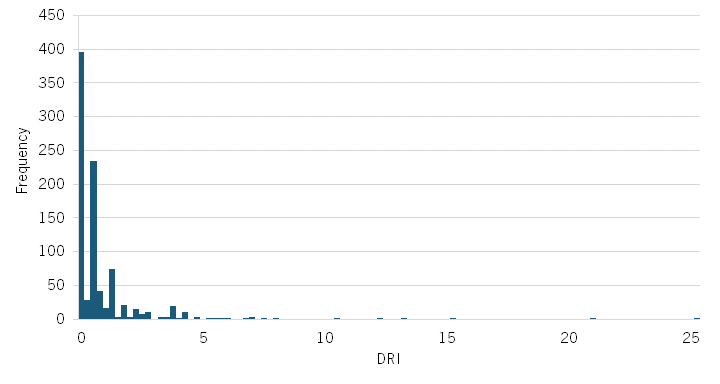

This report’s focus on non-OECD Asian economies means ITIF was not able to use datasets (related to data restrictiveness) as used in past and related models.[92] Instead, ITIF calculates its own data restrictiveness index that measures the weighted running total of a country’s data localization measures up to a given year. Given that not all data localization measures are equally impactful to the economy, a data localization measure is weighted in its count toward DRI based on its directness, d, and the kind of data it restricts, k. Therefore, the data restriction of policy j is defined as:

![]()

See table 4 in appendix B for the possible values for d and k. A data restriction is scaled higher based on how direct it is and how important the restricted data is to the economy. A higher value assigned to a given data restriction imparts that that data restriction carries greater severity. Therefore, a country’s DRI score in a given year is the sum of the data restrictions of its policies in place in that year—that is, if a country c has n data restriction policies in place in year t, its DRI is calculated as:

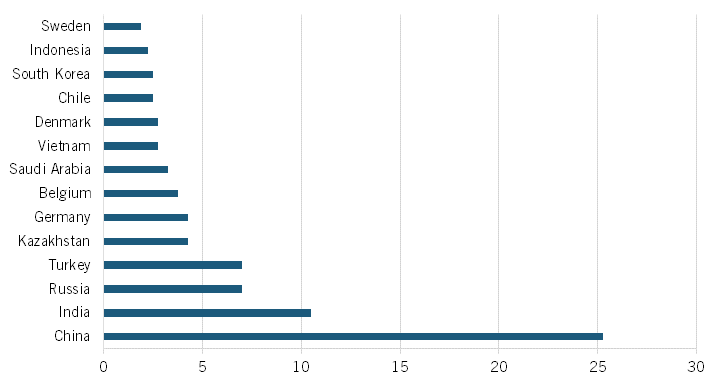

The primary data source utilized to tabulate a country’s data restriction by year of enactment, its directness, and its kinds of data affected is in “Appendix A: List of Data Localization Measures” of Cory and Dascoli 2021.[93] A higher DRI reflects a higher degree of data restrictiveness enforced by a country. Figure 2 shows the most-restrictive economies by way of cross-border data transfers, based on DRI scores for 2020. Following this methodology, data on 64 economies is recorded using data localization measures passed between 1989 and 2020.

Figure 2: Countries with the highest scores in ITIF’s data-restrictiveness index, 2020[94]

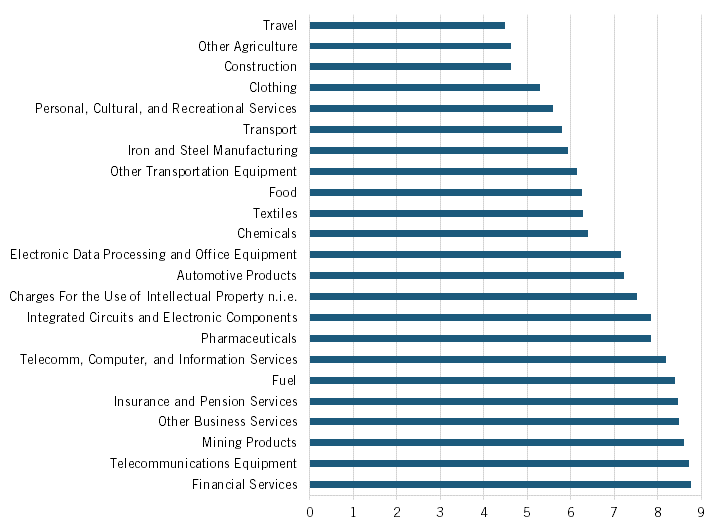

While data is increasingly important to all industries, not all industries are equally reliant on data. For example, firms in finance utilize data far more than do firms in agriculture or home health care. This model assumes that industries more reliant on data are therefore more impacted by the restrictive effects of data localization than are industries with less reliance on data. Therefore, ITIF calculates a data intensity modifier (DIM) to control for differences in an industry’s reliance on data. Like ITIF’s prior study, and other related studies, data intensity is approximated by measuring the software usage per worker in each U.S. industry. The model further controls for endogeneity by using the base year 2013 to calculate DIM, as opposed to calculating country- and year-specific DIMs. This control, however, assumes equal technology among countries and over time. Data for intangible software expenditure per industry is taken as noncapitalized software expenditures listed in the 2013 U.S. Census Information and Communication Technology Survey.[95] This data is divided by the number of workers in each corresponding industry as provided by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for the same reference year of 2013.[96] DIM is taken as a natural log to align with previous literature on factor intensity. That is, the DIM of industry i is calculated as:

![]()

Figure 3 in appendix B shows the distribution of DIM ratios among 23 different aggregate industries.

Because this report is concerned with country-level figures for the five countries of interest, country-level DRLs are needed. Moreover, because this report calculates the country-level effect on trade volumes and imports separately, country-level DRLs for total trade and imports are needed.[97] This requires computing country-level DIMs for both total trade and imports. To do this, ITIF takes the weighted average of the industries’ individual DIMs where weights are industries’ share of total trade or imports (depending on which country-level DIM is being calculated) per WTO Stat data. The equation for calculating the DIM of country c is therefore:

where wc,i is industry i ’s share of total trade or imports in country c. A higher DIM—and therefore DRL—of imports than of total traded goods and services implies that, in aggregate, the country’s imports are from sectors that are more data reliant than its exports. Country-level DRLs therefore allow for some variation in the effects data localization policies have on total trade and import-based sector composition. Appendix B provides a list of each of the five countries’ total-trade and import DIM scores.

Data-intensive industries should be noted as being more susceptible to changes in data localization than are non-data-intensive industries. Therefore, this model provides a score of data restrictiveness for a given industry within a country by linking DRI values with DIM ratios. ITIF draws this linkage as the product of DRI for a given country and year with the DIM for a given industry in order to calculate the DRL for that country’s given industry. Thus, the formula for the DRL of a given industry i in country c and year t is given as:

![]()

DRL serves as a composite index of data localization at the level of country-year-industry. This composite index allows for more precise econometric analysis on the impact of data localization by allowing industry-level comparisons. In this final index, the sample size includes 57 unique countries, 23 unique industries, and observations between 2005 and 2020. The tables providing the full list of countries and industries can be found in Appendix B.

The composite index DRL is tested in separate regression models against response variables indicating trade, while the DRI is tested against a response variable capturing the price of imports and nontariff trade costs (as data for these response variables is not available at the industry level). Given how integral data storage, transfers, and analytics have become in several areas of the economy, ITIF predicts that increased restrictions on the flows of data will suppress trade volumes, since those restrictions limit the use of data to facilitate economic activity and thus trade activity. Data localization, by way of limiting a firm’s access to using data to add value, also prevents foreign firms from entering new markets, making their business operations less productive and potentially unviable. This would imply that not only does data localization have a negative impact on productivity and growth, but it also restricts a country’s ability to increase transactions from leading firms and thus decreases the competition less-productive domestic firms face. Data localization’s suppression of competition may also likely have continued negative effects on productivity because domestic firms, in their now-favored position, will have less incentive to innovate. For foreign firms still trying to provide competition in domestic markets employing data localization measures, the cost of compliance and loss of access to more-efficient business processes would likely increase their costs of facilitating trade, leading to increased prices for their imports. Therefore, four separate econometric models are designed to regress variables of trade volumes, imports, import unit values, and nontariff trade costs against ITIF’s own country-year indicator on data localization DRI and country-industry-year indicator DRL.

Because the impacts of data localization policies likely take some time to affect economic decisions, each regression employs a one-year time lag such that DRI or DRL in one year is used to predict the relevant economic indicator in the next. All regressions are fixed-effects models with dummy variables for country, industry, year, or some combination thereof.

Trade volume is taken as the sum of export and import data in a given country, industry, and year. Data for the response variable is taken from the WTO Stats database under the dataset “International Trade Statistics.”[98] This indicator is reported in current U.S. dollars. Loss in trade volume reflects a country’s loss in transactions and worsened involvement in global trade. Industry-level imports data by country is also taken from this WTO Stats dataset.

Unit import value is taken as an index on the estimated per-unit cost of a country’s imports in a given year based on its expenditures and quantities imported. While not directly a measurement of price, unit import value is very closely related to a measurement of import prices. This data is also taken from the same WTO Stats dataset under the indicator “import unit value fixed-base indices – annual (2015=100).”[99]

Nontariff trade costs are taken as the sum of estimates of bilateral trade costs for a country with all its trade partners. These are nontariff trade costs, meaning costs recorded in this indicator are attributable to transaction costs, compliance costs, and logistics. Compliance costs may exist in the form of fines firms must pay as penalties on prohibited cross-border data transfers, whereas market inefficiencies may arise from foreign firms being unable to operate the most-efficient data-driven business processes and thus incurring higher operating costs than would otherwise be the case under the scenario in which data flows went unrestricted. Therefore, changes in a country’s estimate of nontariff trade costs are induced not by tariffs but by changes in a country’s regulatory and/or logistical framework. This data comes from the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) and World Bank joint database.[100]

Final panel data is merged between response, predictor, and control variables containing a sample of 23 industries, 56 countries, and 15 years. While this would give a maximum number of observations equal to 19,650 entries, the actual number of observations carried out through regression analysis is notably less because of missing data. On regression using DRI as the independent variable in regression, the maximum number of observations for regression analysis would be 840. This model’s final sample size contains entries for several economies, providing a diversity of countries ranging in development, geography, and OECD status. The following are the four primary regression models analyzed, wherein c denotes country, t year, and i industry:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

B0 represents the intercept. B1 is the coefficient for the predictor variable. This coefficient indicates the relationship between data restrictiveness and the selected economic indicator. B2 is the coefficient for the control variable GDP per capita, which estimates the effect that change in GDP per capita incurs on the response variable in question. GDP per capita is only added as a control variable for regressions using DRI as the predictor variable instead of DRL. This control is only needed in those cases where direct change in wealth is required to be isolated in regression models so that the substitution effects of an increase in income are captured. This justification is explained in further detail in appendix B. The dummy variables α, γ, and δ represent country, year, and industry fixed effects, respectively. These fixed effects control for all other unobserved factors that undoubtedly influence response variables that are specific to only either countries (e.g., geography), years (e.g., global economic shocks or trade agreements unfolding over time), or industries (e.g., import intensity). The error term ε captures the residual value between predicted and observed values.

Ideally, the model would be more comprehensive and robust for these countries (to be consistent with past and related reports on data localization), but the lack of data and the sample of countries makes this difficult (e.g., including China and India complicates the relationships between labor productivity growth, the size of the economy, and DRI). In particular, in Cory and Dascoli 2021, the relationship between DRI and total factor productivity (TFP) was analyzed for 28 OECD countries. Unfortunately, TFP data is unavailable for many of the countries in this report (including all the non-high-income countries). Labor productivity, measured in GDP per hour worked (adjusted for purchasing power parity, or PPP), could be used with data from the Penn World Table 10.0.[101] Still, data is not provided for all 57 countries. Just for curiosity’s sake (into the potential impact), ITIF used a subsample of only 36 countries that still includes our five countries and territories of interest; all the countries excluded from this subsample are non-high-income countries. Because of this smaller sample, complications arising from the inclusion of China and India (which assume greater importance in a smaller sample), and the increased relative weight of observations from high-income countries, the model to test the relationship between DRI and labor productivity and the test’s results are presented in the appendix and not in the main results tables.

Regression models show that increased data localization measures yield multiple statistically significant negative impacts on an economy. The regression table estimates negative relationships for trade volume and imports associated with an increase in data restrictiveness, while estimating positive relationships for unit import values and nontariff trade costs. Coefficient estimates for trade volumes and unit import values are statistically significant at the 95 percent confidence level, while imports are statistically significant at the 99 percent confidence level (estimated p-values are less than 0.05 and 0.01, respectively). Coefficient estimates from the log-linear regression provide the percentage changes in response variables associated with a one-unit increase in DRI or DRL.

Table 2: Results of primary regression models

|

Dependent Variable |

Ind. Variable |

Coefficient Estimate |

Pr(>|t|) |

Standard Error |

Degrees of Freedom |

R-Squared |

|

ln(trade volume) |

DRL |

-0.005 |

0.012** |

0.0020 |

17,825 |

0.84 |

|

ln(Unit Import Value) |

DRI |

0.009 |

0.015** |

0.0035 |

805 |

0.52 |

|

ln(Imports) |

DRL |

-0.006 |

0.002*** |

0.0019 |

17,775 |

0.84 |

|

ln(Nontariff Trade Costs) |

DRI |

0.009 |

0.134 |

0.0060 |

702 |

0.86 |

Note: Statistically significant at *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

The model finds that a one-unit increase in an industry’s DRL is associated with a 0.5 percent decrease in its trade volume in the following year. While the most data-intensive industries identified in the model—such as telecommunications and finance—would be most affected, nearly every industry requires some usage of data to facilitate trade and would thus face some degree of loss in trade volumes.

Based on regression findings for this sample, imports are most sensitive to increased data restrictiveness. Increased data restrictions hinder firms’ use of data in activities such as data analytics, targeted advertising, and supply chain management. The regression results suggest that a one-unit increase in an industry’s DRL is associated with a 0.6 percent decrease in its imports the following year.

Regression results suggest that, on average, a one-unit increase in a nation’s DRI is associated with a 0.9 percent increase in unit import value the following year for that country. Assuming the control variable GDP per capita accounts for increases in unit value due to consumers importing higher-/lower-quality products as incomes rise/fall, the coefficient estimate of DRI can be interpreted as a direct association to an aggregate measure of prices for a country’s imports. Therefore, a one-unit increase in a nation’s DRI reflects a 0.9 percent increase in its prices paid on imports in the following year. This effect on import prices is likely the result of a combination of market inefficiencies and compliance costs incurred from data localization measures. These higher costs of doing business for foreign firms from increased data localization would expectedly result in a rise in import prices passed along to buyers.

As further evidence that increased import prices are the result of rising trade costs incurred from data localization, regression analysis on the log transformation of nontariff trade costs reports a positive coefficient estimate. A one-unit increase in DRI is associated with a 0.9 percent increase in national aggregate nontariff trade costs among its trading partners the following year. Though the estimate is not statistically significant at the 90 percent level, it is consistent with the original hypothesis and the statistically significant estimated effect on import costs.

An increase in import prices coupled with a decrease in imports suggests that data localization constitutes a supply constraint for imports, consistent with the original hypothesis. That overall trade volume decreases in line with (but slightly less than) imports suggests that exports, too, are affected by such policies. This is unsurprising given that imported intermediate goods are often used in the production of final goods for exports, in which case the data localization policies also constitute a constraint on the country’s exports.

In recent years, data localization has unfortunately increasingly captured the attention of policymakers in Asia. To illustrate what these estimated costs associated with increasing data restrictions may look like for those policymakers, ITIF extends its econometric findings to model costs of various proposed and enacted data localization measures for Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Vietnam.

In analyzing all the policies listed in this report, the model estimates that Vietnam’s measures are the most restrictive, followed by Bangladesh’s. (See table 3.)

Assuming that these policies are adopted and implemented over a five-year period, and assuming that the countries’ DRI scores increase at a constant rate each of those five years, ITIF extends its econometric findings against the average annual change in DRI per country during a five-year period. Due to rounding, the total DRI increase does not always equal five times the average increase. Expected changes in the response variables at the end of the five-year period are reported.

It’s worth recalling that the DRI is the country-level measurement of data restrictiveness. Meanwhile, the DRL is a measure of the restrictiveness at the country and industry level (using proxy data from the United States on how different industries use data to different degrees via the Data Intensity Modifier, or DRI). To determine the effects on a country’s trade and imports, country-level DRLs are computed using the country’s weighted-average DIM, where weights are industries’ shares of total trade or imports. Since each country’s trade profile is different, country-level DRLs allow for some variation in the effects data localization policies have on total trade and imports. A higher DIM—and therefore DRL—of imports than of total traded goods and services implies that, in aggregate, a country’s imports are from sectors that are more data reliant than its exports.

Table 3 provides estimates of the economic impacts of data localization anticipated in these five country case studies. Note that nontariff trade barriers are not included in the table. This is both because of the lack of statistical significance at the 90 percent level and because the estimated effects on nontariff trade costs are approximately equal to those on import prices.

Table 3: Effects of data localization policies after five years

|

Country |

Change in Data Restrictiveness Score |

Change in Import Prices |

Change in Imports |

Change in Overall Trade Volume |

|

Bangladesh |

+2.0 |

+2.0% |

-7.7% |

-6.0% |

|

Hong Kong |

+1.6 |

+1.5% |

-6.8% |

-5.7% |

|

Indonesia |

+1.8 |

+2.0% |

-6.9% |

-5.8% |

|

Pakistan |

+1.1 |

+1.0% |

-4.7% |

-3.7% |

|

Vietnam |

+2.8 |

+2.5% |

-10.8% |

-9.0% |

Based on the estimated annual change in Bangladesh’s DRI implied by its current proposal, ITIF estimates that Bangladesh’s level of trade will be approximately 6 percent lower after five years, with imports being 7.7 percent lower. Bangladesh’s import prices are also expected to be 2 percent higher.

For Hong Kong, while estimates do not address any active legislation and only speak to a hypothetical plan, costs are still indicative of the economic burdens that could be incurred from a base data localization policy. Hong Kong’s trade volume and imports would be roughly 5.7 percent and 6.8 percent lower, respectively, after five years and its import prices would be 1.5 percent higher.

Indonesia’s increased frequency of data localization in recent years also brings notable consequences. Adoption of these policies is associated with a 5.8 percent decrease in trade volume and a 6.9 percent decrease in imports after five years. Indonesia’s import prices are expected to be 2 percent higher after the five-year period.

Of the five countries of interest, Pakistan is the one proposing the least-restrictive data localization policy; however, it’s still expected that after five years, its trade volume will be 3.7 percent lower, its imports 4.7 percent lower, and its import costs 1 percent higher.

In contrast, Vietnam’s data localization policies are the most restrictive of the five countries considered. Its data restriction policies suggest that trade volume and imports would be 9 percent and 10.8 percent lower at the end of the five-year period, respectively. Import prices are estimated to be 2.5 percent higher.